California Salmon

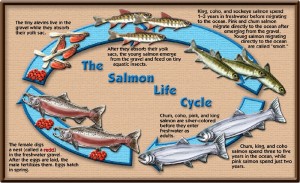

Salmon are one of our most iconic species in Northern California. Not only an important resource for the people of Mendocino County, but they also play many roles within our coastal ecosystems. For our community, they provide a source of income, recreation, nutritious food, and culture. Within the ecosystem, salmon are unique in many ways. They are an anadromous species, which means they hatch in freshwater streams and rivers, migrate to the ocean for feeding and growth, and return to their natal waters to spawn and die. After spawning, their carcasses contributes vital nutrients to the streams and its inhabitants. Their survival depends on healthy forests, rivers, and oceans. There is no other fish that better defines our region.

5 Species of Pacific Salmon

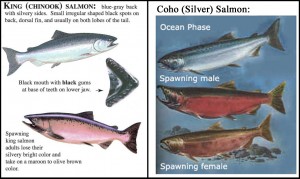

Although it doesn’t look like it in the image above, in the ocean, Chinook and Coho salmon are very similar in appearance. These fish undergo drastic changes in appearance at different life stages. When fishing, it is important to be able to differentiate between the two species because Coho salmon (also known as silvers) are considered an endangered species, and are therefore illegal to possess at any time. Some key differences between the species include:

- Chinook have black lower gums, whereas Coho have white gums around the teeth and darker gums inside the teeth.

- Chinook have smooth caudal fin rays, and Coho have rough caudal fin rays. If you run your thumbnail against their tail, a Coho tail will feel similar to the edge of a dime.

- Chinook have large black spots on their upper back and on the whole caudal (tail) fin.

- Coho have small black spots on their upper back and only on the top of the caudal (tail) fin.

Follow this link to learn more about the endangered Coho Salmon.

Diet

The diet of young salmon (called fry) includes mainly plankton, invertebrates, and insects. After reaching maturity, adult salmon feed of other fish, squid, eels, and shrimp. Sockeye salmon have a unique diet that is almost completely comprised of plankton. Salmon returning to spawn stop eating completely once they get to fresh water.

Reproduction (spawning)

Salmon may travel as far as thousands of miles to return to the same waters where they hatched to spawn. Ideal salmon spawning habitat are small streams with stable gravel substrates. Adult female Chinook, for example, will prepare a depression called a redd (or nest) in a stream area with suitable gravel composition, water depth and velocity. The adult female may deposit eggs in 4 to 5 “nesting pockets” within a single redd. After the male fertilizes the eggs, the female uses her tail again to cover the area and then she will guard the redd from just a few days to nearly a month before dying. Chinook salmon eggs will hatch, depending upon water temperatures, 3 to 5 months after deposition. Eggs are deposited at a time to ensure that young salmon fry emerge during the following spring when the river or estuary productivity is sufficient for juvenile survival and growth.

In the Streams: Salmon spend up to the first half of their life cycle feeding in streams and small freshwater tributaries. For Coho, that’s 1-3 years, for Chinook it is anywhere from 3 months to 1 year. After they absorb their yolk sac, they then feed mostly on aquatic insects. Estuaries are important habitat for small fish to feed.

Migrating to the Ocean: As the time for migration to the sea approaches, juvenile salmon lose their “parr marks”, a pattern of vertical bars and spots useful for camouflage, and gain the dark back and light belly coloration used by fish living in open water (this coloration helps them blend in when viewed from above or below). Also, their gills and kidneys begin to change so that they can process salt water. Once at sea, they transition to a diet of mainly fish. Adults return to their stream of origin usually at around three years old. Some precocious males known as “jacks” return as two-year-old spawners.

Chinook salmon are easily the largest of any salmon, with adults often exceeding 40 pounds. Some individuals over 120 pounds (55 kg) have been reported!

Threats

Salmonid species on the west coast have experienced dramatic declines in abundance during the past several decades as a result of various human-induced and natural factors. There is no single factor solely responsible for this decline, given the complexity of the salmon species life history and the ecosystem in which they reside. Certainly we know that coastal development in California has created a significant number of barriers to migration in our rivers as we develop road and dam waterways. A lot of effort has gone into removing or replacing these barriers, particularly in the 5 northern California counties (explore the 5C Program for example), as well as replace lost habitat in our rivers and streams. However, much less is know about salmonid oceanic life stages, and how ocean variability will effect the survival of a particular year class of fish. Research is beginning to look at ocean temperatures, productivity and circulation patterns to try to improve the management of healthy salmon populations.

For more information, please the NMFS Pacific salmonids threats page.